Stem Cell Donors Australia was formerly known as Strength to Give and ABMDR. Learn more.

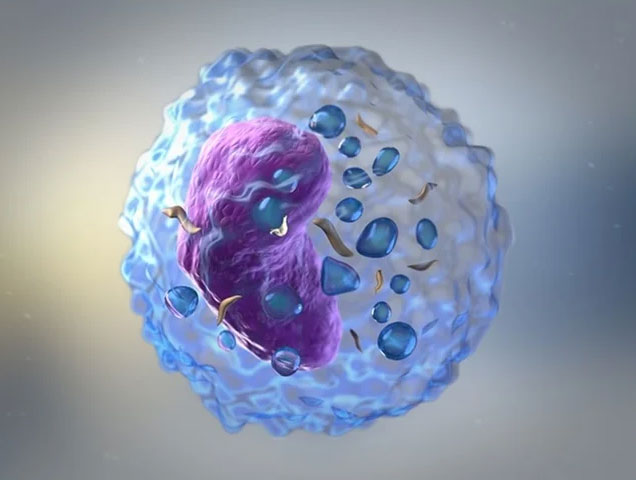

You may have noticed that we now refer to transplants as ‘blood stem cell donations’ rather than ‘bone marrow transplants.’ This change reflects the fact that most donations today come from the bloodstream, rather than directly from the bone marrow.

While bone marrow transplants were once the primary method, medical advances have made it possible to collect blood stem cells from a donor’s bloodstream in a process called Peripheral Blood Stem Cell (PBSC) donation. This method is less invasive and accounts for the majority of donations, with approximately 9 out of 10 donations being performed in this way.

‘Blood stem cell donation’ is hence a more accurate and inclusive term that reflects the full range of modern donation methods.

Blood stem cell transplantation has come a long way since it was first imagined in the late 19th century. What started as a radical idea has evolved into a life-saving procedure that gives thousands of people a second chance each year. As a member of Stem Cell Donors Australia you’re connected to this incredible history, one shaped by innovation, persistence, and scientific breakthroughs.

In 1891, researchers proposed that bone marrow extracts could be used to treat leukaemia. But it wasn’t until the devastating effects of World War II that medical science began to seriously explore transplantation. The war revealed that radiation exposure could destroy bone marrow, leading doctors to consider whether healthy donor marrow could be used to restore patients’ immune systems.

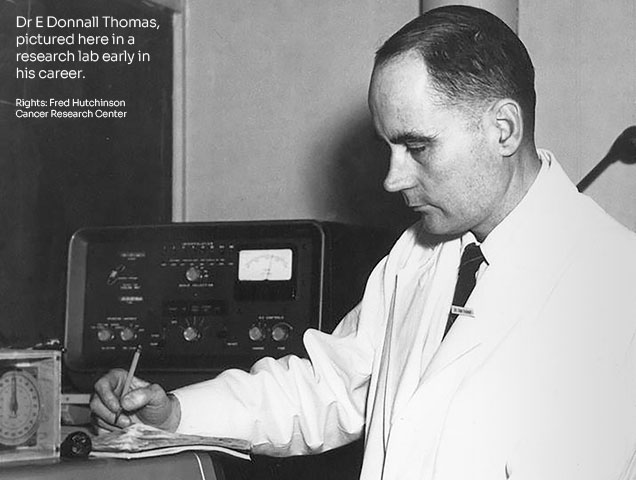

Dr. E. Donnall Thomas, a young physician with a vision, set out to make bone marrow transplantation a reality. In 1956, he attempted the first human transplants, using radiation to eliminate diseased marrow before infusing donor cells.

Unfortunately, the early procedures were unsuccessful. However, Thomas’ work laid the foundation for future breakthroughs, and in 1990, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions.

A major obstacle to successful transplantation was the immune system’s natural defense against foreign cells. In 1958, scientists identified Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLAs), proteins on cell surfaces that determine compatibility between donors and recipients. This discovery led to the first successful bone marrow transplant between non-identical siblings in 1968. The patient, a young boy with a rare immune disorder, survived thanks to a transplant from his sister, proving that a genetic match could make transplants successful.

The next challenge was finding matches beyond immediate family members. In 1973, a two-year-old boy in England became the first person to receive a bone marrow transplant from an unrelated donor. His mother’s efforts to find a match led to a community-wide search, highlighting the power of donor registries, a concept that would later become essential for saving lives worldwide.

News of this successful transplant encouraged Shirley Nolan, the mother of a child with a rare genetic disease called Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, to search for an unrelated donor for her son, Anthony. Although a match was never found for Anthony, her efforts led to the creation of the world’s first bone marrow donor registry, which was named in his honor.

By the late 1970s, doctors were successfully treating inherited immune deficiencies with bone marrow transplants. But for leukaemia patients, the procedure was still a gamble. Many doctors abandoned the idea after initial failures, but researchers refused to give up. In 1979, the team at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, led by John Hansen, performed the first successful transplant from an unrelated donor to treat leukaemia, proving that this approach could work. Around this time, researchers also developed better ways to prevent graft-versus-host disease, dramatically improving patient survival rates.

As bone marrow transplants became safer and more effective, attention turned to finding ways to match more patients with compatible donors. This led to the creation of national and international donor registries, allowing patients to find matches beyond their immediate families.

Today, over 40 million people worldwide are registered as potential donors, making it more likely than ever that a patient in need can find a life-saving match.

Every major breakthrough in bone marrow transplantation has been driven by research, perseverance, and, most importantly, donors. By being part of the Australian blood stem cell donor registry, you’re continuing this legacy. Whether or not you’re ever called to donate, your commitment makes a difference.

Medical science continues to push boundaries, exploring ways to improve transplant success rates and even eliminate the need for full genetic matches. The future is bright, and you’re a part of it.